- Home

- Ian Stuart Sharpe

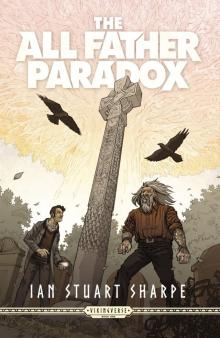

The All Father Paradox

The All Father Paradox Read online

VIKINGVERSE: THe All Father Paradox

Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com

Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler

Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott

Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors

Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or fictitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specified. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Published by Outland Entertainment

5601 NW 25th Street

Topeka KS, 66618

ISBN: 978-1-947659-52-0

Worldwide Rights

Created in the United States of America

Editor: Shannon Page

Cover Illustration: Jeremy D. Mohler

Cover Design and Interior Layout: STK•Kreations

For my wife, who has Thiassi’s Eyes

EXEGESIS I

GOSFORTH, ENGLAND

2017

WELL, YOU TOOK YOUR TIME!”

The roaring complaint was so unexpected that Churchwarden Michaels dropped his freshly printed parish circulars. The gale swept them up and chased them across the churchyard, pink sheets flapping between the moss-bound tombstones, like confetti at a giant’s wedding.

“Jesus!” Michaels scrabbled on the worn slate floor, preferring to salvage his photocopies over his dignity. There was little hope of either. The coastal winds were merciless in winter and howled at the churchwarden in derision. He gave up and watched the last of his newsletters wing their way across the countryside to roost in far-distant hedgerows.

“I hope you don’t keep your God waiting this long.” The voice that had startled him was clear above the wind.

The churchwarden swallowed his irritation and peered out of the gabled porch. An old man stood by the Viking cross, unmoving in the storm, wrapped in a plain grey cloak. He was tall, burly even, but still the cross towered over him, a slender scratch against the bruising sky.

The churchwarden grimaced, summoning the courage to brave the weather.

“I’m sorry,” he called out, “did you have an appointment?”

“What is the date today?”

Michaels was amazed at the lungs on the old chap. He could really project.

“November eighth. Have you got the wrong day? Happens to the best of us.” The churchwarden practically bellowed, shrugging to emphasise his point in case it got lost in the bedlam.

“No, I am exactly on time,” the visitor said.

It was commonplace for visitors to appear in the churchyard at all hours. The Viking cross seemed to defy time as stalwartly as it withstood the elements. Even the name was stubborn—he’d long since given up trying to explain that calling all the Northern tribes víkingar was like saying all Englishmen were pirates. No, Vikings were in vogue. All kinds of people paid their respects—although nowadays it was generally hikers on their way to Scafell Pike or sightseers checking off historic sites from Visit Cumbria guidebooks. Only academics made appointments, and the vicar’s wife hadn’t mentioned anything about special guests today. Besides, other than his long beard, the old man didn’t seem especially professorial.

Michaels sighed deeply. He had no choice in the matter. He’d have to conduct an impromptu tour. He was custodian of a grade-one listed building, and that came with responsibilities, or so the reverend had said, not just to God, but to the fabric of society. You only had to glance at the newspapers to know that the world was becoming a little frayed around the edges. Community, shared heritage, those were the only things that could mend it.

A stitch, in time, saves nine. Armed with that thought, the churchwarden begrudgingly left the safety of the porch and huffed and puffed towards the visitor as fast as he could. He took a deep breath.

“Reverend Riley normally invites guests from the university to meet him at the rectory—” he shouted, struggling to be heard, “—for a nice cup of tea and a chat first.” He let the thought trail into the wind, realising mid-sentence it was a forlorn hope.

He ought to preserve a modicum of respect. This was hallowed ground, after all, and he didn’t want to wake the dead. Most of the tombstones dated back centuries, to when St. Mary’s was reconstructed in 1789, and he supposed if he made enough of a ruckus, he might disturb the two ancient chieftains entombed below the church itself.

Tea, he reflected, would be especially welcome on a day like today. Michaels had always thought it a shame to leave the cross standing out in the British weather. One thousand years of this, it was a miracle that it had survived at all, but there it was: a wealth of detail carved into fifteen feet of red sandstone, round at the base, rising to a square top with a cross head, each of the four sides carrying images of a horseman, dragons, serpents, and all kinds of gorgeous, interlaced patterns.

The old man didn’t respond. He walked around the column, examining all sides. Close up, he looked like stone-made-flesh, weathered certainly, but also uniquely carved, with withered tattoos intricately woven over his face and arms.

Michaels kept a discreet distance. He didn’t mind heathens. Ásatrú or Forn Sed, they called themselves, the worshippers of the Old Ways. Neopagans, the newspapers said. Either way, they went with the territory. Admittedly, it was a little odd to find them venerating their long-dead deities on parish soil, but Reverend Riley always reminded the laity that the Church of England was a tolerant church. St. Mary’s must strive even harder, he insisted, in this day and age, especially after the referendum. If the drugs or the drinking got out of hand, a quick call to the Cumbria constabulary was all that was needed to move them along.

This man though… there was something belligerent about him. Something wild. He looked like a contestant on Neo-Nazi’s Got Talent, , arms emblazoned with the symbols of the progenitor race. That was the other sort Michaels had to deal with. Soldiers of Odin they called themselves; mean streaks, full of piss and vinegar, telling anyone who would listen that they’d turn back the tide of immigrants, send everyone back where they came from. In fairness, Mrs. Jones had said much the same thing at the Parish Council last month. It had fallen to Reverend Riley to point out that her beloved Vikings were immigrants to these parts themselves.

Michaels decided to try his own voice of reason.

“Beautiful, isn’t it, the cross? I have a pamphlet inside the chapel if you’d like to know more.”

If he could get the man out of the storm, so much the better. He might be able to hear himself think. There was still no reply. Instead the man continued to prowl around the pillar.

“Are you from the museum? The V&A?” Michaels probed.

“Jorvik,” the old bear grunted at last.

“Ah, Jorvik! The Viking Centre! Have things recovered after the flood? I went to York Minster and saw one of the temporary exhibits.”

The churchwarden was delighted to have placed the visitor. The York Archaeological Trust did all kinds of work in the community, even sending actors on tour. That would explain the booming voice. Authenticity, that was the key, even if things went a little askew when looking down the long lens of history.

“In that case,” Michaels continued, “Heill ok sæll, be happy and healthy, Mr.… I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your name.”

The old bear offered a sly smile.

“You speak the Northern tongue, do you?”

“Well, churchwardens in the Anglican Communion are legally responsible for all the property belo

nging to a parish church. I like to think I have a duty under ecclesiastical law to keep up to date on everything to do with the cross and the people who made it.” He was starting to go hoarse. “As the Bard said, ‘How far that little candle throws his beams! So shines a good deed in a weary world.’”

“The eighth of November,” the man said. “There is a saint whose feast day it is?”

“Well, we don’t really go in for all that business at St. Mary’s, but you are right. One of yours as it happens. St. Willehad of Bremen. Well, he was the first Bishop of Bremen, but he was an Englishman. Local chap, born in York. Placed in charge of converting the Saxons, sometime… well, before this cross was carved. Escaped a big rebellion, if I remember correctly.”

“Very good, Churchwarden. That is quite right.” He seemed lost in thought.

Old age comes to us all, thought Michaels, and he was about to prompt the man further when he emerged from his reverie and spoke.

“My name is… Chandler.”

Michaels brightened, then felt compelled to explain. “One of my favourite authors, Chandler. In fact, I’m currently rereading The Long Goodbye for the eighth or ninth time. Terrific stuff, that.”

Michaels was brimming with enthusiasm, so much so that he barely noticed the wind drop from an anguished howl to a conspiratorial whisper.

The visitor held him with a steely gaze.

“You like detective stories, Churchwarden?” Chandler said. “Well, as it so happens, I’m embroiled in one myself. I am looking for those who murdered me. In fact, I’ve sent someone to bring them to justice.”

BOOK ONE: FATE

NORTHERN SAXONY

ANNO DOMINI 782

In principio creavit Deus caelum et terram.

[In the beginning, God created Heaven and Earth.]

FOLKWARD SMILED, WATCHING THE INK bite into the parchment. A new copy of the Holy Writ, a fundament waiting to be filled with wonder.

The old monk looked up from the manuscript and exchanged glances with Hemming, his genial companion, who was eagerly smoothing parchment with his broad hands. Folkward blew softly on his forefinger, and the novice dutifully stretched across the table to pass a fresh candle. Simple signs for the simple life engendered by vows of silence.

Folkward’s smile rarely wavered these days. As the candle flickered into life, he carefully slid his goose quill into the phial and bent his head back to his task. It was the precision that he relished—two columns to a page, a continuous flow, letter on letter, word on word, until he reached the neatly ruled margins. He scratched large, clear, beautiful letters, each one a joyful spark of creation. There were frequent pauses, dabs of fresh ink, time to stand back and savour. Time to enjoy the intimacy, the sense of surrender that came with inking His word.

If pressed, he would confess to a modicum of pride in his work. His eyesight was undimmed, his fingers still nimble—and his penmanship was renowned, or so he was told. Kings and potentates across Christendom asked for Folkward by name; and for these talents, he was grateful. They were worth a touch of backache. He did worry a little about how his shoulders hunched—he seemed to slouch even when standing tall or singing full-throated at Mass—but considered the matter a trifle in the bigger scheme of things. He was a vessel for the divine; such was the price of allowing His Word to direct his quill.

Hemming busied himself arranging the manuscript’s pages into gatherings of eight and pricking the pages with a small knife to mark the highest numbered page, shaping each folio. The silence was amiable, each monk content in the halo of his candles. Folkward glided across the page as the spirit of God moved over the waters.

Terra autem erat inanis et vacua et tenebrae super faciem abyssi et spiritus Dei ferebatur super aquas.

At the edge of his hearing, there was a stirring toot of a hunting horn, although the Saxon boar-chasers with their long spears and sallow dogs often simply herded the slowest and most wobbly old sow in sight. The hogs were certainly at their fattest now.

Folkward’s stomach growled in anticipation. In just a few weeks, sides of delicious bacon would be hung in the rafters, making a virtue of the smoke that thickened the air. The first crop of onions, leeks, and celery would soon be hauled from the garden. Next year, there would be fruit from the orchard. Better still, bees had settled in the thatch, which would mean all the riches of honey and an end to the pungent aroma of tallow candles—burnt mutton fat and fresh pigshit made an unholy, cloying alliance. The September harvest would soon be matched by the woodland bounty of beechnuts, acorns, chestnuts, and other fruits of the forest. No wonder his belly seemed rounder with every passing year.

The forests were the most bounteous portion of the Saxon lands, showing the sheer detail of His creation. Folkward found it fascinating. Take the oak tree, for instance. It was like a Book of Genesis unto itself, providing the ink the monks curled across the page in such intricate fashion. A wasp had once gnawed into the wood to lay its eggs, and then, in self-defence, the tree formed a gall around this rude intrusion, circular and hard-skinned, bulbous like a crab apple. It was Hemming’s job to crush the oak galls in vinegar, thicken them with gum arabic, then add iron salts to colour the acid and get the mixture ready for the labour ahead. You couldn’t help but wonder at the majesty of creation, revealed and replicated even in nature’s minutiae. It was sobering to think that the Lord provided everything, even the means to copy Sacred Scripture. Folkward pondered for a moment, then realized that the Lord had even provided Hemming. He chuckled at the thought and arched his back, feeling his spine and shoulder blades crack.

He looked back to Hemming, now rustling around the book chests. The novice was an ungainly fellow, not quite comfortable in his own skin, but Folkward loved him all the more dearly for it. Hemming wore the ground-length tunic of undyed wool given to every novice, belted, but still so loose and ranging he was prone to sweeping every room he entered. His sleeves, three quarter length on most monks, hung all the way to his wrist. A Dane by birth, Hemming bathed at the well every Saturday, as was the custom with his people. Folkward had named him Hemming the Heaven-Scent when he first arrived although, of course, he never uttered the phrase aloud.

The Dane went barefoot, in penance for whatever mischief brought him to the abbey five years before. Folkward heard from some huntsmen that Hemming had stolen fruit as a young man, but he hadn’t pried; his vows required him to avoid unnecessary speech and gossiping about a man’s past transgressions fell squarely in that category. Even in his habit, the young man would smile at every Saxon woman that passed, but in all other matters, he was a model convert, a quick learner, and a fond favourite of all the monks. Folkward trusted the Lord would forgive the flirtation as a foible.

Dixitque Deus: Fiat lux. Et facta est lux. Et vidit Deus lucem quod esset bona: et divisit lucem a tenebras.

Hemming hovered nearby until Folkward finished the verse, then delivered some welcome refreshment: a wooden cup, brimful of mead. The blessed bees—God’s cattle indeed! It was probably time to take a short break. His stomach could use the exercise. Folkward made the sign of the cross, nodded his head in thanks, and then beckoned his companion outside, down the short corridor to the courtyard. He stretched a little and then sat down next to the well, surveying their own parcel of creation, brimming with life and dappled by the evening sun. By the grace of King Karolus, Folkward and his fellow missionaries had brought light where there once was only pagan darkness. That was why they were here, after all, at the very edges of the kingdom. A Royal Commission, to bring the Saxons before God now that the Saxon War had brought them to heel. He peered into the trees past the stables but couldn’t see any sign of the hunters. They were lazier than the swine.

My cup runneth over. He grinned as he sipped his drink, trying not to let it spill. The old monk had come a long way from his days as an earnest young scholar in York. This place was a delight, especially when it was quiet. When the brethren fell into silent prayer, the bees buzzed, the wood pigeon

s cooed, and you could take pleasure in all its subtle variety.

The monks were never idle. Ora et labora—to pray and work. That was the life of a monk. Benjamin, Artrebanus, and Genoald would educate the young while Folkward and Hemming copied manuscripts, illuminated the missal, and transcribed the gospels. Others cultivated the soil, guided the plough, planted vines, bound iron supports to the oak shaft of the watermill. Genoald was soon to fire glass for the chapel in his charcoal furnace.

They had built the monastery with a practiced eye—seeking out the proper site for their new monastic home, making sure that it stood close to the Saxon tribes and that it had fertile soil and the benefit of a coursing stream. And then, with a prayer, trees had been felled, a well was dug, and buildings began. They blanketed the sturdy beams and planks with willow branches and then daubed the walls with clay, straw, and dung. Through their toil, they heralded the Kingdom of Christ, whose holiness redeemed the bodies as well as the souls of His creatures. The monk’s songs of praise, echoing into the ancient glades, had tamed the ancient Saxon forest. His song, from Matins to Compline, was the channel by which they spoke to God, its rhythmic beauty an act of homage. The monks were practicing for the glorious day when they would stand in His presence.

The monastery was visible proof that progress had been made, and not just at the point of the king’s swords. Over five years of holy toil and perhaps heaven-sent good luck, the brethren had built churches, ordained priests, and made so many converts that, after two years, hardly an idolater could be found in all the lands between the Weser and the Elbe. If the king’s favour was true, there would soon be a new bishop in the nearby town of Bremen, the first diocese in this part of the world. Brother Willehad’s cathedral already had the first beams in place.

The horn blasted again, closer this time, although still lost in the trees. Birds startled into the sky, shrieking in caustic reply to the martial sound. Folkward drained his cup hurriedly and set it down on the grass. He paced back, round through the chapel and library then back to his desk. Perhaps it wasn’t hunters after all. Perhaps it was the king’s outriders, attending to their safety. That was not a welcome thought. Folkward found himself easily irritated when his peace and quiet was disturbed. That was the problem with an abundance of contemplation, it made the mind restless. He reached over to the Master Bible, his source, and traced his finger down the second column, searching almost to the end of the leaf, until he came to the words:

The All Father Paradox

The All Father Paradox